<- Back to Natstats

NATSTATS Dashboard Explained

Intro \ Backstory

I spent a lot of my day job as a data organizer creating infographics

for IT technical teams and management to get everyone on the same page. This dashboard is another iteration of that

work history and attempts to get riders and organizers on the same page

regarding is an event ‘easy’ or ‘hard’.

Certainly, every rider has their opinion of what is easy and what is

hard. Here we attempt to put some common

structure around those opinions and draw some lines around what’s ‘easy’,

what’s ‘hard’ and expand the thinking to define what’s ‘just right’.

Each year the NATC sends out a survey to the riders and one

of the questions on the survey asks - is an event too easy or too hard? This specific question was bothering me in a

couple of ways. I know as a reader I was having to work too hard to figure out

what the results were trying to tell me but I also had lots of questions:

-

are

the results skewed in some way since not every rider responds to a survey?

-

what

is 'easy', what is 'hard'?

-

which

line(s) of the event are too easy or too hard?

-

what

are the organizers goals for a national event?

-

what

are the riders’ expectations for a national event?

-

is

the rider in the right class?

-

etc.

More questions than answers really so after the 2021 October

meeting I set about figuring out a way to improve on it. This process doesn’t in any way

discount the value of the rider survey, rather the intent here is to perhaps

find a better way to view and evaluate the results of this specific

question.

“Come on let’s dive in already Jonesy….” (Blue italics is my buddy Goober who

came over to go riding.)

Disclaimer: Though I do play an official role in the NATC organization

(I’m the current web admin for mototrials.com) NATSTATS is a completely

separate activity that is my own unsanctioned, independent and creative work

for infotainment purposes only. It is

in no way an official representation of the thoughts or opinions of the Council

(though most think it is ‘pretty cool’).

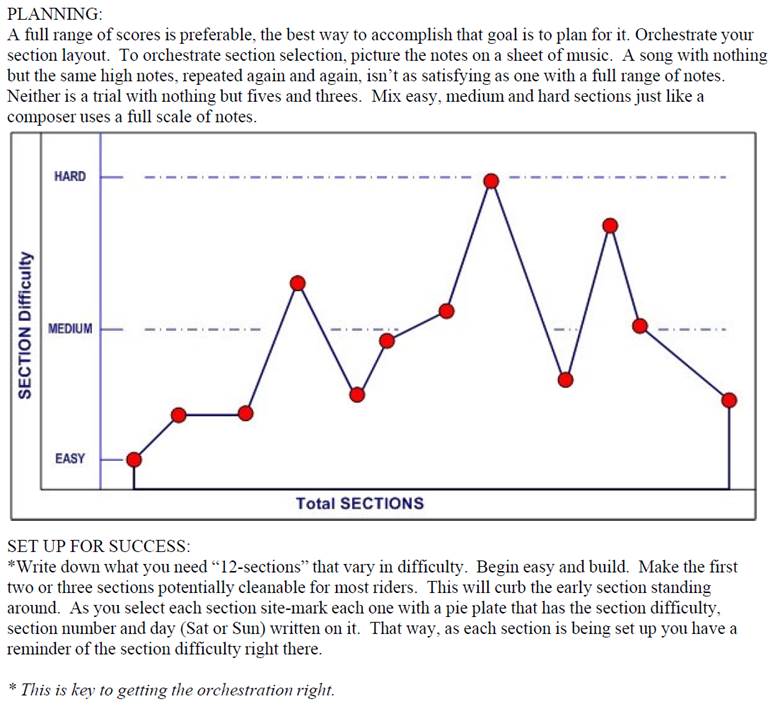

For starters, in case you didn’t know, the NATC organizer

handbook provides guidelines for creating a successful event as shown

below. Basically, a mix of easy, medium

and hard sections. The rider’s scores

are then a reflection of how well the trialsmasters, clerk-of-the-course and

sporting steward did in laying out the course.

“That’s cool”

Of course, weather can be a factor as well raising the difficulty

level significantly even on the best laid out courses but at the end of the day

the rider survey question and this dashboard act as part of the ‘score card’

for the organizers.

First - The Numbers

The color-coded dashboard uses the rider's actual scores as

their 'vote' this way every rider is represented; every line is represented and

every 'vote' is counted.

Actually, almost every 'vote' is counted. If a rider has a statistically extremely high

score or extremely low score relative to everyone else then we exclude those

scores from the calculations. Exclusion

is done using a statistical formula so there is a consistent way to evaluate

the scores versus someone’s subjective opinion. For the math heads out there, we use the Interquartile Range (IQR)

Method with the

R_7 estimate type and interpolation scheme.

This

method seemed like the best fit for our needs and can also be done in Excel

using the QUARTILE.INC() function (“Come on

Smalls you’re killin’ me here - ZZZzzzz…”) . For the conspiracy theorists out there, it’s

an algorithm with a bias in it – deal with it 😊.

The process takes all the finishers’ scores, excludes any

statistical outliers, sums up them up, takes the average and divides by the

number of sections ridden to get the Average Points Per Section for each

line. Digesting just the numbers still

requires some mental math so the next step applied some color coding to make

the chart easy to read at-a-glance. (“I’m not so good at math but I like finger

painting.”)

Second - The Colors

The color-codes more represent the everyday rider

experience. 80% of entrants ride to have

a good time, hang out with their buddies, challenge themselves against the

course and let the chips fall where they may.

Then there are the 20% of riders that show up to compete for every point

and the level of difficultly doesn't really matter - they'll work through it -

the only thing that matters to them is beating the next rider by 1 point. That said, here is where the model ‘draws the

lines’ for the different color levels:

·

The

blue represents a technically easy (but mentally challenging) ride where any

little point taken can move you down the leaderboard pretty quick.

·

The

two shades of green represent what could be considered the 'sweet spot' for a

national. While 80 points might feel a

little heavy to some - it is a national.

It’s okay to be challenged as long as it isn’t dangerous. (“Roger that

Mr. Pocket Protector.”)

·

Yellow

and up just get more physically and mentally challenging. Other factors, like the weather, can come

into play and blow out the scores more.

That said, yellow may be okay for the top two or three lines but going

yellow on the bottom 2 lines (which is 70% of the entrants) and attendance is

likely to drop off.

Third – Usage

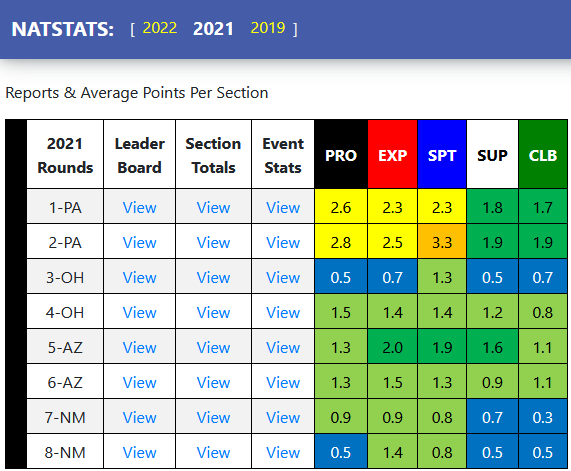

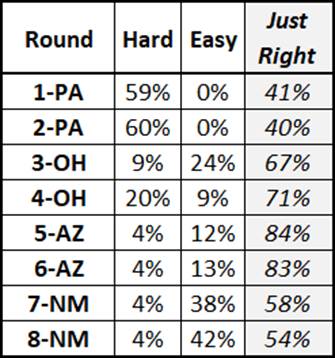

After applying the algorithm and colors to the 2021 data -

over 900 riders and over 43,000 ‘votes’ later - we get the easier to read at a

glance dashboard which closely aligns with the rider survey results (note that

I added the ‘Just Right’ calculation to the survey results). “That’s a

colorful story. I get it now. Are we going riding soon?”

Rather than focusing on any one-color block, the dashboard

should be looked at as a whole.

Organizers can use it to consider what if any changes are needed and riders

can consider and maybe adjust their expectations of what is easy, hard or just

right but both sides are seeing a common view.

Like trials, it is all a balancing act.

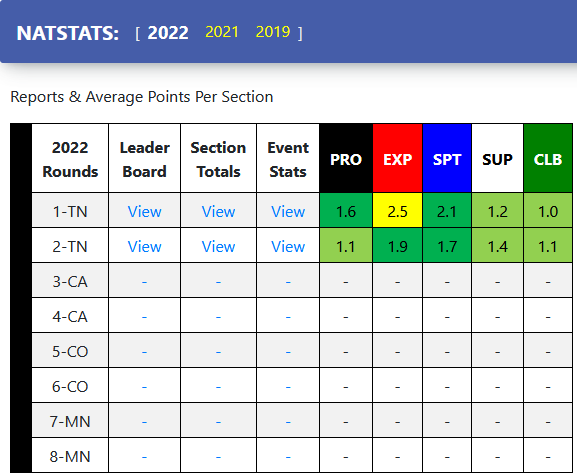

Going forward and with the process established, the dashboard

can be updated shortly after each event to provide near real-time feedback and

insight as the season progresses.

Some Outlier Examples

These examples will show how the exclusion process works. (“Exclusion? Doesn’t Ford make those?”) While exclusions may seem overly complicated

and, in some cases, doesn’t move the needle that much, it is necessary to have

a consistent exclusion process. The

extreme scenario was in 2021 where a rider was having some issues and scored

the maximum of 180 points while the average for the rest of the class was just

27 points. If we included the 180, the

average points per section would have been 1.2 but with exclusion the average points

per section is just 0.6. Lastly (“Thank you Lord!”), exclusion doesn’t happen

as much as you might think - 900+ riders in 2021 and only 28 exclusions

(3%).

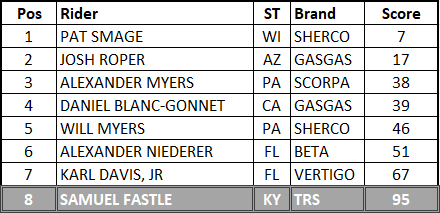

2022 Round 2 in Tennessee - 1.052 average points per section a fun day of riding (“Pat’s my hero.”)

·

If

we do the straight up math, we have a total of 360 points \ 8 riders \

36 sections = 1.25 average points per section

·

If

we exclude outliers, we get a lower bound of -.625 and an upper bound of

88.375 so we’ll exclude Sam’s 95 points to get a total of 265 points \ 7 riders

\ 36 sections = 1.052 average points per section (which rounds up to 1.1

on the dashboard)

·

A

decrease in the rating of .2

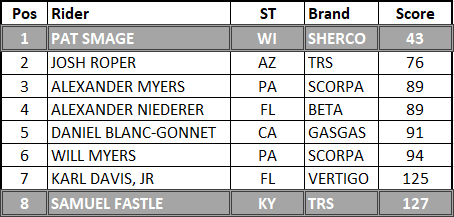

2021 – Round 1 in Pennsylvania. Somewhat of a rare

situation so it is interesting to look at

(“Whatever you say pocket protector…”) an exclusion on both the

upper and lower bounds yields a 2.61 average points per section a hard

yellow day of riding but they are Pros they can handle it. Exclusion of the low score doesn’t happen

very often but when it does it’s usually in the Pro class and under difficult

conditions which shows greatness separating from goodness. (“Oh well that is kinda interestin’”)

·

If

we do the straight up math, we have a total of 734 points \ 8 riders \

36 sections = 2.55 points per section.

·

If

we exclude outliers, we get a lower bound of 61.75 and an upper bound of

125.75 so we’ll exclude both Pat’s 43 and Sam’s 127 points to get a total of

564 points \ 6 riders \ 36 sections = 2.61 average points per section

(which rounds up to 2.6 on the dashboard)

·

A

small increase in the rating of .07

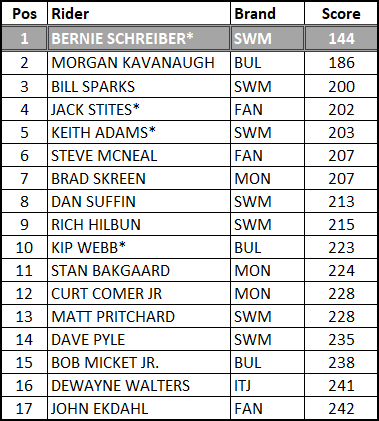

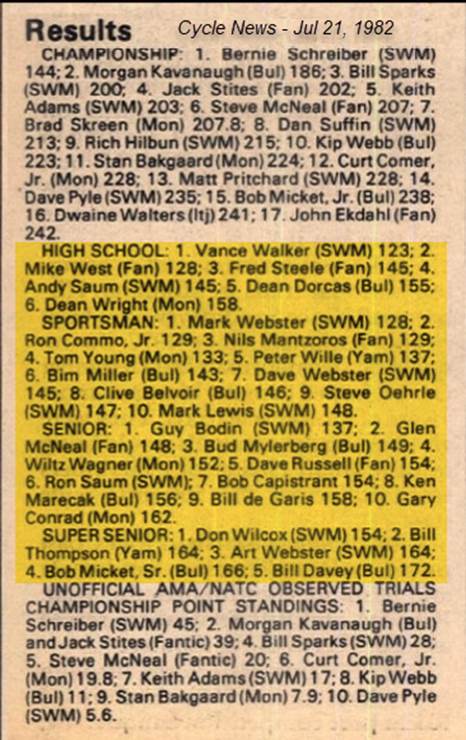

1982 – Whitefish, Montana. The highest

scoring trial in NATC history - 3.64 average points per section a

grueling orange day of riding and another example of greatness separating from

goodness.

Of course, things were a little different in 1982 – 20

sections x 3 loops and challenging weather conditions blew out the course. But using the algorithm we can compare the

past to the present. Also, it is

interesting to note how many future NATC Hall-Of-Fame riders attended this

event.

* NATC Hall Of Fame members

·

If

we do the straight up math, we have a total of 3636 points \ 17 riders \

60 sections = 3.56 points per section.

·

If

we exclude outliers, we get a lower bound of 165.5 and an upper bound of

265.5 so we’ll exclude Bernie’s 144 points to get a total of 3492 points \ 16

riders \ 60 sections = 3.64 average points per section

·

An

increase in the rating of .08

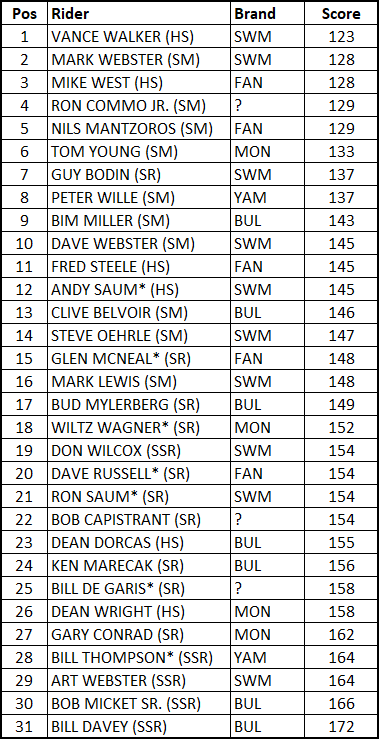

Okay last one I promise (“Wait

you said the last one was the last one?”) – This is what Red looks like - 4.11 Average Points per Section. The Support line at that same 1982 Whitefish,

Montana event. They rode 12 sections x 3

loops so a max of 180 points - just like today.

“Dude, that’s a lot a points right

there.” The sections were so

slick and blown out that in some cases riders just ‘took a 5’ and moved on so

I’m told.

* NATC Hall Of Fame members

Note the older rider got the benefit of doubt for any tie-breakers.

·

If

we do the straight up math, we have a total of 4583 points \ 31 riders \

36 sections = average 4.11 points per section.

·

In

this case there are no exclusions lower bound is 116.75 and upper bound is

178.75

Wrap-Up

There you have it, a look at the dark arts behind this

points-based approach to evaluating each line at an event.

HUGE shoutout of THANKS to all the checkers, the scoring

crews, the data entry folks and the techno wizards that create all the data

making this fun little exercise possible.

Comments, questions and\or concerns can be addressed to natstats@tutanota.com

“Okay that wasn’t too bad geek squad, now let’s

go ride!” Indeed let’s go!